Throne room and finale

The next milestone was the weather station on the summit of the south dome. We started our new course with renewed energy, but as the days went by it became clear that the wind was dying and on its last breath as we approached the summit from the north. Little by little, our goal of reaching the weather station on the south dome became more and more complicated.

We couldn’t make it.

In order to finish the journey on what we thought might be a new nunatak, we had to make a steep attack from the east to the dome. And that meant going further south than we could get back from later on to get to the summit.

Having made it to the DYE3, we didn’t mind missing this little milestone so much. After a few days of absolute calm, treacherous slopes, and a few other difficulties, we set off on our return journey in a stroke of good fortune, which allowed us to cover quite a few kilometers in the last five days. Approximately 400 km. As the return journey took considerably less time than the outward journey, I want to tell you now a little about the science projects and how they suffered (together with the human who carried them out) along the way.

The Universidad Autónoma group’s project, microairpolar, turned out to be my pet experiment: most days I would start the collectors just before going to sleep and get up a few hours later to remove them. During that time, any organisms that had been flying through the arctic air would be trapped in my “lollipops,” which are just removable sections of the collectors that I store once I’ve used them. I put in a new lollipop, let it sit for a few hours, and store it in sterile conditions so that my lab buddies could get the microorganisms fresh, alive and kicking.

It wasn’t particularly fun waking up at 5:30 am to remove the lollipops with latex gloves on, let me tell you. But one does what one must.

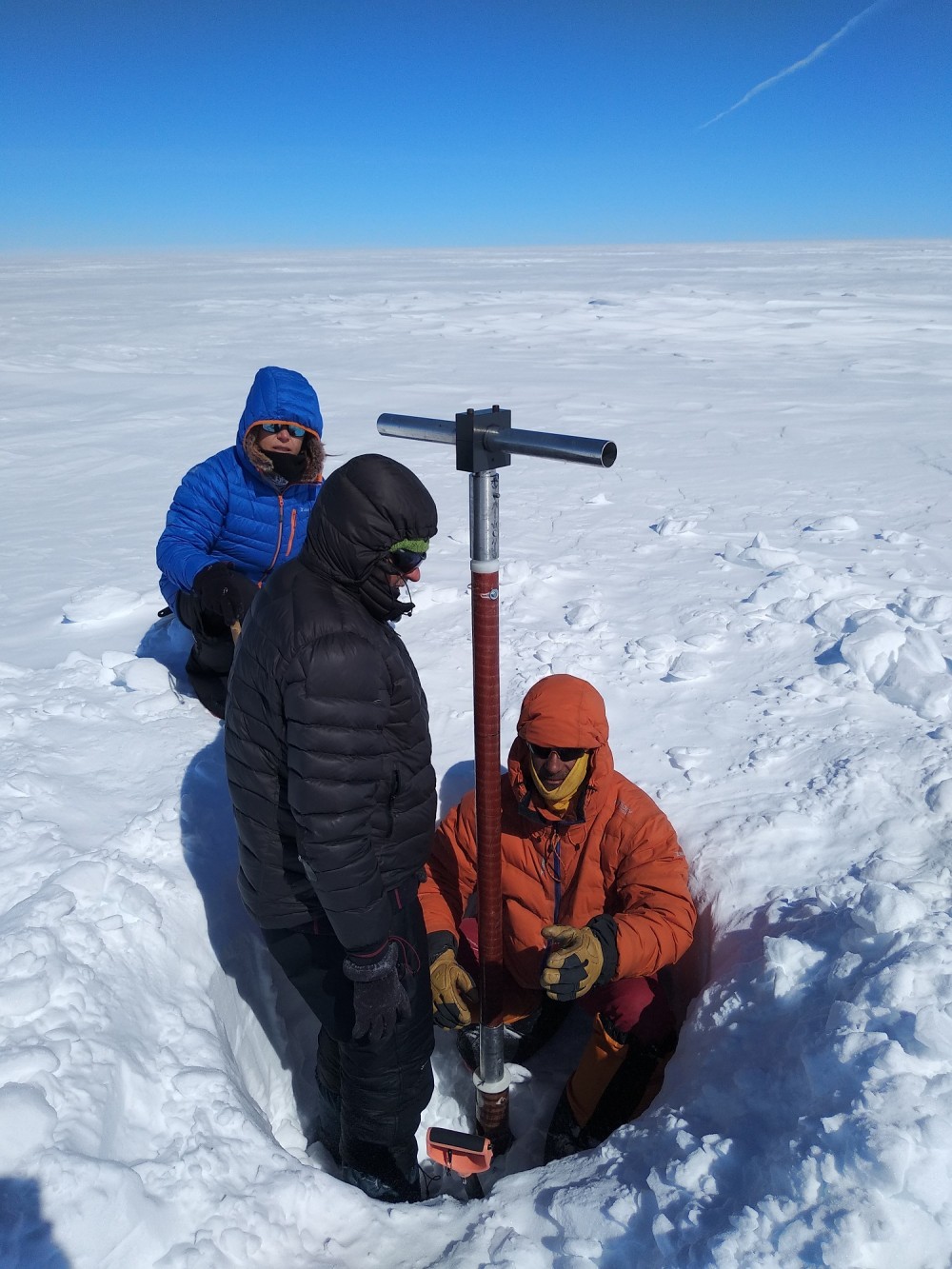

The Astrobiology Center project involved a slightly more physical, less psychological routine. Armed with an ice core drill provided by the famous glaciologist Paul Mayewski, I had to take ice cores several meters deep at different points along the journey. I would melt and filter the cores and then keep these filters so that my colleagues in the laboratory could study them after my return to Madrid.

However, after the drill broke on the first day, the outline of the samplings changed slightly.

And yes, when we discovered that the drill had broken I cursed in many different languages (some made up) and spent two hours digging out the last half meter of ice, which turned out to be a band so hard that it had jammed the device and caused it to break. There I was, crouched down three meters below the surface in a 60-cm-wide hole, muttering “Paul Mayewski’s drill, I’ve wrecked Paul Mayewski’s freaking drill...” as I chipped away with an ice axe in a state of anger and frustration. Now I’m telling you about it jokingly, but at the time I was very upset by what had happened. My teammates helped me over the psychological hurdle and we devised an alternative plan. Unfortunately it boiled down to “we’ll have to dig instead of drill.”

So all the sampling we did for the SOLID project involved digging 2-meter-deep holes, sterilizing a wall, and coring out the ice transect and the ice profile from there.

We definitely had to put our backs into it.

SOLID was not the only experiment to give us trouble, though. My laptop, where I was downloading the meteorological data from the microairpolar experiment, left this world for five days in the middle of the expedition. We consulted by satellite phone with Ignacio Oficialdegui, our expert for these things, who suggested that it could be a problem with the humidity that sometimes builds up inside the living quarters module. His recommendation was to put it on the cooker for a while. My first reaction? I ought to censure myself. Let’s sum it up as “no.” Finally, and keeping my distance, I put it on the cooker for a few hours, but there was no change.

So I took out my secret weapon, which I had been sharpening for a long, long time: the 30 sachets of silica that I had been collecting from packaging of all kinds since I decided to make this expedition to the Arctic. Any chemist out there knows how useful silica is for drying; it can even rival that little cup of uncooked rice we put our flash drive in after it has spent a cycle in the washing machine. Drying power over 9,000.

And so it was that I welcomed my beloved laptop back to the world of the living, grinning from ear to ear with satisfaction for putting the thousands of euros I spent on university tuition fees to good use, and at last for something serious, though with absolutely no one to share my satisfaction with. The scare had passed.

FYI, the laptop died again at the end of the expedition and the sachet trick worked again. Amazing.

And so, putting out little fires here and dodging windless black holes there, we arrived at our final location: a new nunatak. My teammates went to explore it while I finished the last samplings and Ramón named our discovery: Windsled’s Harbour. Location: N 61º 46’ 03”, W 45º 42’ 44”. A clear sign, sadly, of the rampant rate at which the ice masses comprising our ice caps, especially the Arctic ice cap, are disappearing. A bittersweet reminder of the biggest problem we face as a species today: global warming.

Our beloved Mads, the helicopter pilot, took us off the ice on the 14th with great pleasure. On the first flight he took Juanma, Bego, and me, who got to take the co-pilot’s seat. When we were about to go from the glacier to the coastal mountains, he asked me “Do you like Start Wars?” through the helicopter’s internal communications system. I said, “Yeah, I love it.” He then began a steep sideways descent into a rock gorge. We were obviously recreating Luke’s attack on the Death Star. Already overjoyed that after a month I could finally take a shower that day, I reached a level of happiness that I can’t put into words. In my mind, the song from the throne room (the end of A New Hope) started to play and I let out the typical “wooooow” squeal that one lets out on these occasions. I guess I got a bit of American dramatic spirit from my time at the DYE3, but it was, getting some of my Madrid spunk, mazo cool and I couldn’t hold it in.

Back on solid ground, at the hostel where we showered and slept for the next few days, I ran into none other than Paul Mayewski, whose drill I had broken. Paul, who is a very good friend of Ramón’s, was with a group from the University of Maine doing some sampling along the south coast. Rest assured that he forgave me, saying that it was no great loss and that he himself had broken many drills in the past. He’s very nice, that Paul, that’s what I think.

This adventure was as well-rounded as the DYE3 dome set against the horizon. The emotions I felt, the moments I spent with my teammates, and my own personal growth are as intangible as they are immeasurable and valuable. Everyone at GMV helped make this happen and for that priceless gift I will forever be grateful. More than I can express here.

Thank you very much from the bottom of my heart.

Author: Lucía Hortal